A little over a year ago, I gave the following presentation at the Appalachian Studies Association as part of a panel regarding dark sky preservation and a dark sky park in Grantsville, WV, Calhoun County. My goal was to establish that dark skies are and should remain a part of the Appalachian sense of place. My actual talk also included a few slides regarding light pollution. I only include one of those below.

Under West Virginia Skies

I grew up in a small town located in the heart of the Appalachian coalfields. Or as the late author John O’Brien described McDowell County in his book At Home in the Heart of Appalachia, “the heart of the heart of Appalachia.” Welch, West Virginia sits nestled into the steeply rising banks and hillsides adjacent to the Tug Fork River and Elkhorn Creek. Our house was the seventh one on the right as you left town heading south on Route 16. The front porch sat fifteen feet back from the narrow, shoulder-less road, which sees its fair share of hulking 18-wheelers weighted down with heaping loads of black coal. The neighbors across the road lived in houses perched 60-80 feet above street level. The uncommon nature of the topography of my home environment seemed to me as nothing extraordinary, until one summer, I had a few college friends from Emory & Henry home for a visit. One afternoon, as we were heading out of the house, my neighbor across the street, fired up his lawn mower. Now, I had grown up watching Carl cut his grass by lowering the mower down the hill with a rope cleverly tied to its handle. So I paid him no mind. On the other hand, my friends from Chattanooga, Gate City, and even Clintwood, evidently did not have neighbors who cut their grass using the “rope technique.”

While my friends and I still laugh about this revelation, it illustrates something special about this region and why it is so quintessentially, Appalachian. In Welch, and McDowell County more generally, the mountains feel particularly close. Standing on my “postage stamp” of a yard – the only nearly level spot in my neighborhood – mountains steeply rise in every direction. The Sun is visible for short periods of the day as it crosses a narrow river of blue sky. In the late afternoon, it ducks behind the mountain to our west, hours before it actually sets. Darrell Scott describes the phenomenon perfectly in his song “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive” as he sings, “The Sun comes up about ten in the morning and the Sun goes down about three every day.”

As a young boy, I remember looking up at night seeing a river of darkness replace the blue of the day. I remember watching Taurus and Orion and the occasional planet wander across the sky. My narrow window on the Universe became as much a part of my sense of this place as the feeling of comfort provided by the closeness of the mountains during thunderstorms or the chill from the damp air that occasionally settles into the valleys late on a summer night. A “sense of place” can be a difficult concept to articulate, often being no more than a sense of longing for a place one lives or has lived in the past. For me, Tal Stanley’s The Poco Field: An American History of Place helped to make this concept more concrete by giving me a critical lens through which to see and understand my own sense of place. He defines a person’s “sense of place” as the “result of a prolonged interaction and interrelationship between three complex realities,” which includes the natural environment, the built environment, and human culture and history. The natural environment means the topography, geology, and resources of a place. The built environment includes a “human response and appropriation of the land” and resources for “subsistence, profit, and power.” Human culture and history describes the “way of life” of a place and is the result of the interaction between people and the natural and built environments. If you have not read Tal’s book, it is simultaneously a recognition and a critique of two competing desires that many of us struggle to reconcile regardless of where we are from. The first being a desire for the monetary and economic success defined by a corporate dominated, capitalist economic system. The second being the connection and commitment we develop for the places in which we live. Chasing the corporate-defined notion of success requires a willingness to uproot at any moment. In preparation for imminent dislocation, we refrain from developing attachments to places, people, and communities.

For the far-reaching Appalachian diaspora, there is a strong connection to this place that appears to only grow stronger with the passage of time. The “Hills of Home” are never far from my mind. And for me, and other native McDowell Countians like author Homer Hickam, that sense of place includes a dark, albeit narrow sky, populated with stars, planets, and the hazy glow of the Milky Way, as part of the natural environment.

I no longer live in Welch. Currently, I am a professor of physics and astronomy at Colgate University, a small liberal arts college located in the geographic center of the state of New York. The nearest city is Syracuse, which is over an hour away. It is not difficult to find a dark location on campus or just outside of the Village of Hamilton where the Milky Way is easily visible on a clear night. Having lived in Nashville and Charlottesville for a total of twelve years, I do not take this fact for granted. A large number of Colgate students come from New York City and the surrounding, sprawling metropolitan area. It took me a few years to appreciate just how little time the overwhelming majority of my students had spent looking at the night sky. Perhaps, this is because there isn’t really much for them to see back home because of the severity of the light pollution. As a result, most of our students have no personal connection to the sky. It was not part of their “sense of place” connected to where they grew up.

As part of my introductory astronomy course, I require the students to do some naked-eye observing as well as peering through small telescopes at planets, nebulae, and the moon. Without fail, upon first arriving to an observing session, I have several students ask about the cloud in the sky that doesn’t seem be moving. For many these evenings mark the first time they have “knowingly” cast their eyes on the plane of the Milky Way galaxy. The same goes for seeing Saturn and the Moon through a small telescope. These experiences have illustrated for me just how much we in the developed world are losing our connection with sky. For my students and most of the world’s population, the night sky is not a recognizable part of the natural environment and the place they are from.

(Slides: The light pollution found in a big city is enough to obscure all but the brightest of objects like planets, a handful of stars, and the Moon. The recognizable patterns of constellations are washed away in the background glow from light scattering off of particles afloat in the air.

You may have seen one of these images of the Earth taken from a satellite like this composite image that shows nearly the entire globe at night. Apparent are the most densely populated and industrialized parts of the world. The eastern half of the United States is well lit as is much of Europe… and the coastal areas.)

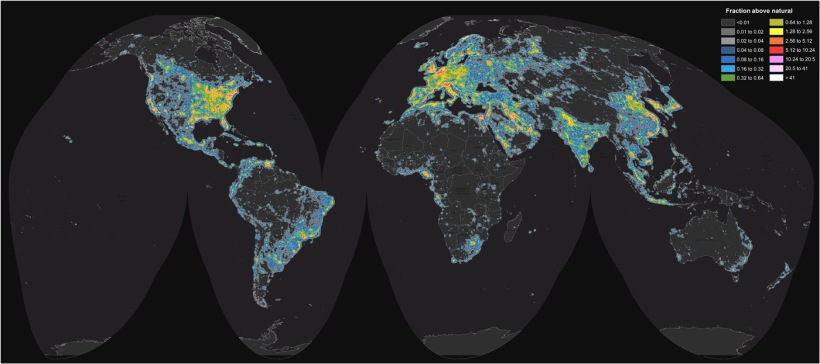

“New World Atlas of Artificial Sky Brightness” F. Falchi (2016)

“New World Atlas of Artificial Sky Brightness” F. Falchi (2016)

Closing

I have a colleague in the department of physics and astronomy at Colgate, Anthony Aveni, Russell Colgate Distinguished Professor of Astronomy and Anthropology and Native American Studies. He is one of the world’s foremost experts on ancient Mesoamerican cultures and the integral role the night sky played in the lives of these indigenous people. The studies of what ancient peoples knew about and how they interacted with the patterns and motions made by objects in the sky fall under a discipline commonly referred to as archeoastronomy – a discipline Professor Aveni is credited with helping to found. In his book, “People and the Sky,” Tony laments the modern world’s lost intimacy with the sky. Where people once saw a reflection of life played out in the heavens, our modern scientific mode of creating knowledge and understanding reduces the once relatable universe to a lifeless, inanimate backdrop lacking any immediacy or connectivity. For ancient peoples from regions spanning the globe, Tony infers “Their astronomy was lived as much as practiced, and much of what our predecessors included in its domain served what we might regard as social and religious rather than scientific purposes.” They lived with a sky filled with representations that were both tangible and familiar.

There is no doubt that our modern world has lost this type of connection to the sky. I’m not here to provide reasons for this disconnection, nor to take measure of what has been and continues to be lost, but to make real and personal the threat posed to future generations and their interest in the sky. Dark sky preservation such as that which we propose in Calhoun County West Virginia is about preserving spaces on this planet where people can maintain a deep connection to the sky, one that becomes an important part of the natural environment and takes root as a sense of a particular place. I argue that dark skies have always been and should continue to be a fundamental aspect of Appalachia, one as important to the local population as the hills, trees, rivers, coal seams, coal miners, and mountain musics.

March 2017